|

| Sam Sykes |

|

| Mark Hodder |

|

| M. D. Lachlan |

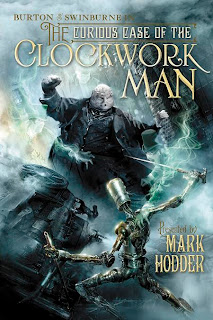

Joining us this month are Mark Hodder (The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man), M.D. Lachlan (Wolfsangel), and Sam Sykes (Black Halo.)

-How much planning do you do before you write?

Mark Hodder: I use Scrivener on my iMac to organise my early thoughts and the subsequent research. After laying down a very basic skeletal structure for the novel, I begin to outline specific scenes which I then shuffle until they fall into the most appropriate sequence. I do a lot of research, and the results from this are hung on the bones of the story. Before anything resembling a cohesive plot has been worked out, I start writing up the scenes, and in doing so themes emerge that lead to new ideas, new scenes, and, finally, the beginning, middle and end of the story. Drafting the novel involves maybe one step back for every three steps forward, because I revise as I progress.

Sam Sykes: I once sat on a panel with George R.R. Martin who brought up the concept of writers as either "architects" or "planters," the difference being that one plans out absolutely everything about the story and adheres vigorously to a blueprint while the other just sort of shoves an idea into the earth and sees how it turns out. When asked which I was, I said I wanted to be an architect. And it's true, I dearly do wish I could plan out everything ahead of time and know how everything was going to happen. But sometimes, things happen.

When authors say they're not really in control of what they write, it's not necessarily some lazy artistic answer to get out of explaining a difficult question (it's definitely part that, though, slovenly bohemians that we are). Rather, it's a consideration of all motives, events and character actions up until that point when their past and their desires conflict with what they should do.

Hence, I would love to be an architect. I draw up my blueprint. I lay my foundations. But somewhere along the line, a stray seed falls out of my pocket. And when the book is done, vines have overrun my yard, the grass is dry and the daisies are flesh-eating kudzu, there is a pack of weasels that has taken over the guest room and I somehow managed to wall up grandpa and we never discovered him until grandma started complaining about the smell.

When authors say they're not really in control of what they write, it's not necessarily some lazy artistic answer to get out of explaining a difficult question (it's definitely part that, though, slovenly bohemians that we are). Rather, it's a consideration of all motives, events and character actions up until that point when their past and their desires conflict with what they should do.

Hence, I would love to be an architect. I draw up my blueprint. I lay my foundations. But somewhere along the line, a stray seed falls out of my pocket. And when the book is done, vines have overrun my yard, the grass is dry and the daisies are flesh-eating kudzu, there is a pack of weasels that has taken over the guest room and I somehow managed to wall up grandpa and we never discovered him until grandma started complaining about the smell.

M. D. Lachlan: Not enough. I normally begin with a phrase, something evocative that sticks in my head. It can be a snatch of dialogue. I write mainstream fiction as well and I had intended to write a modern comedy of manners - or lack of them - when I sat down at the desk. I then started writing about a werewolf. This was a big surprise to me as I had no plans to write fantasy. As I liked what I was writing, I kept going. Because Wolfsangel went - appropriately enough, if you know the story - through several incarnations before it reached its final form the original phrase that began it all is no longer in the book.

Normally I pile in to the writing immediately and let the characters evolve. When I hit a sticking point then I might start to plan a bit. As I'm writing historical fantasy I do a great deal of reading but that's not the same as planning. I also continue to read as I write and put ideas in as they emerge. My technique is to over-write and then to edit. So Wolfsangel was 200,000 words when I began, clipped back to 15,000 and expanded again to nearer 140,000. If I planned I might have saved myself this considerable effort. But you write how you write and planning has rarely worked for me. I do read novels and listen to music to get into the mood I want and to remain in it over a period of up to a year in which it takes to write the book. For Wolfsangel I read the Norse sagas again, Icelandic fairy tales, Franz G Bengtsson's The Longships, Jean Rhys's Wide Sargasso Sea - for its sense of inescapable destiny and simmering menace - quite a lot of Angela Carter, and listened repeatedly to a favorite album of mine - Dreams Less Sweet by Psychic TV, in particular the track "Thee Full Pack."

-Do you find stories begin more from a character, a setting, or something else?

MH: The characters, definitely. Often I intend that a character will do something, only to find, as I write, that he/she wants to do something else. This is why it's important for me to have a very vivid picture of who my protagonists are, of what motivates them, of how they act, and so forth. They have to be as near alive as possible, so they can take control of the story, reacting to events in a manner in keeping with their personality. My job is to throw circumstances at them that steer them towards the various crises and resolutions the story demands.

SS: Character. Duh. They shape everything. Setting is great and all, but, at its best, it's a conflict for the characters to overcome. There's always going to be a lot of talk about world building and society-crafting and magic systems and how the people of the ancient culture of Wha'defuk are at odds with the upstart nation of Everythingtoprovistan over the proud tradition of anal oratory, but unless it affects the characters, it doesn't do anything but distract the reader.

Granted, there are traditions of world building, traditions prouder than even the most suggestive anal orator, and it's deeply ingrained in fantasy readership. It's not a matter of choosing character or setting, but rather finding out how each culture, each ruin, each kiss and each curse is significant. No one reads a story for a history exam.

Granted, there are traditions of world building, traditions prouder than even the most suggestive anal orator, and it's deeply ingrained in fantasy readership. It's not a matter of choosing character or setting, but rather finding out how each culture, each ruin, each kiss and each curse is significant. No one reads a story for a history exam.

MDL: Like I say, normally a phrase, or a snatch of dialogue which leads on to a character. I then work out what my character wants the most in the world and make sure that they don't get it. I like to pose my characters virtually unsolvable problems, things that compromise them and challenge them right at the core of who they are. If you can do that then the story comes quite easily. Sometimes a character will say something I didn't expect them to, or a small character will assume a bigger part. That's one of the most exhilarating experiences in writing - it feels like you've just met a new and exciting friend. Or a new and exciting enemy.

-How is writing a second book different than writing a first book?

MH: I had no idea whether I was capable of writing a novel when I worked on The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack. The fact that I achieved it, it got published, and it had a positive critical reception, meant I was far more confident with The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man. Also, the various criticisms of Jack provided very useful guidance in terms of what to avoid and what to accentuate in Clockwork, so I hope the second book is better than the first.

SS: Not a lot. The plot changes drastically, stakes are increased, loincloths are added. Ideally, each book should be its own story.

MDL: Sometimes harder, sometimes easier. In this case it was easier. I had the mythology worked out, knew who wanted what and what was going on. The second book of the Wolfsangel series wrote itself, really. Writing is a game of pot luck sometimes. You have to start and hope interesting characters emerge. That happened almost instantly in Wolfsangel and in the sequel - Fenrir. I'm hoping it happens in Book III too.

-What are some of your favorite genre tropes? How do you use them or subvert them in your own work?

MH: I think there's a very thin line between a trope and a cliche, so I'm cautious in my use of them. Steampunk, I would say, is perilously close to becoming cliche ridden and needs to now develop beyond the signifiers that have established it as a distinct genre. I love the trappings of steampunk; the mechanical contraptions, the manners and rituals of society, the stiff upper lippedness of its heroes and heroines. But, also, I see these as themes that need to be poked at and pulled apart, so, for example, in my Burton & Swinburne novels the machinery is not only always breaking down but is also causing great cultural upheavals; society is blatantly unjust; and my heroes are badly flawed and might be making the problems worse rather than better. As for the principle icon of steampunk, the airship: I avoid it.

SS: I guess I quite like the idea of romance in fantasy as a trope. It was common enough that the roles of fantasy characters could be summarized as Brave Hero, Cunning Sidekick, Wise Mentor and Girl. Female characters existed primarily to be love interests and that was roughly all that was going on. Counterculture struck back with females who didn't give a crap about men and/or relationships born out of a practical need for sex. Some of them worked, some of them didn't. I thought both kind of sucked. Romance is not easy; it's awkward, angry, violent and frequently sticky (metaphorically and not). It's a conflict, one that we're inherently more invested in.

Close behind is the idea of fantasy races. In many, you seem to have each race fulfilling a role: proud warrior, shrewd merchant, wise ancient, and girl. Often, those labels were about all we ever got to go on, and they're frequently alarmingly divided into good and bad roles (humans walk like THIS, orcs walk like THIS). To define an entire race by a label and have everyone agree with it is to remove another layer of conflict and thus, cheapen the story. I quite like the idea that, with races being as diverse and often wildly different from the standard human in fantasy novels, they sort of don't get along. Why would elves, long-lived and dwindling, just accept that fate rather than blame it on expansionist humans? Why would dwarves bother with either of them and not, instead, develop a severe, paranoiac police state due to their isolationism?

The thing is, I don't think these are subversions. Fleshing out a romance and filling out a culture so that neither are hollow and meaningless seems more like something that should just be done.

Close behind is the idea of fantasy races. In many, you seem to have each race fulfilling a role: proud warrior, shrewd merchant, wise ancient, and girl. Often, those labels were about all we ever got to go on, and they're frequently alarmingly divided into good and bad roles (humans walk like THIS, orcs walk like THIS). To define an entire race by a label and have everyone agree with it is to remove another layer of conflict and thus, cheapen the story. I quite like the idea that, with races being as diverse and often wildly different from the standard human in fantasy novels, they sort of don't get along. Why would elves, long-lived and dwindling, just accept that fate rather than blame it on expansionist humans? Why would dwarves bother with either of them and not, instead, develop a severe, paranoiac police state due to their isolationism?

The thing is, I don't think these are subversions. Fleshing out a romance and filling out a culture so that neither are hollow and meaningless seems more like something that should just be done.

MDL: I like what GRR Martin does with multiple characters - an extension of the Lord of the Rings split fellowship sort of thing and I certainly write from the point of view of a few different characters in my books.

I like a lot of fantasy where the characters are self seeking or mean but I don't write it. In my books virtually everyone is trying to do the right thing. I think there are very few truly evil people in the world and my writing reflects that. Fate sets the characters as enemies and they take it from there. Destiny looms very large in the Norse world view and so it does in the world of Wolfsangel. A lot of the characters are fighting to be normal, to be small and ordinary, against the grand destiny that has been set for them.

There's a lot of talk at the moment about the separation between traditional high fantasy and the newer 'gritty' fantasy but I don't see myself as on one side or another. I'm trying to do something that's solidly connected to myth and which hopefully picks up some resonance from that. I try to do ordinary, convincing characters who reflect the outlook of their time. I'm not interested in subverting anything - I just want a powerful, honest story with a big emotional impact - a human fantasy rather than a gritty or a heroic one. My influences here are people like Alan Garner, Ursula Le Guin and Marion Zimmer Bradley - somewhat old school, I know. Also, like these writers, I want a story that is complete in one novel. There are other ways to link a series than leaving the reader - who has paid good money for your book - with a sack of unresolved plot issues on the final page.

The werewolf in Wolfsangel might be seen as a subversion of the traditional werewolf, I suppose. It doesn't change with the full moon, takes months rather than minutes to transform, is unaffected by silver, doesn't make other werewolves with its bite. It's actually truer to the mythic idea of the lycanthropy - which is a condition brought on either deliberately, through sorcery, or inflicted through a curse. The werewolf who transforms with the full moon is largely an invention of Hollywood. Even Lon Chaney's Wolfman in 1941 doesn't change at full moon. Again, though, I didn't set out to subvert this idea of the modern werewolf, I just drew on what I knew from the Norse myths and a different sort of creature emerged.

-Seen any good movies lately?

MH: Hollywood is regurgitating so much tripe, bilge, and drivel these days that I have despaired of ever seeing a good movie again. Then along came The King's Speech and I was blown away. I simply loved that film! In general, though, I think there's far more original, entertaining and creative material on TV than in the cinemas. For comedy, Modern Family and Episodes are hilarious. For detective shows and costume drama, British TV is experiencing something of a resurgence at the moment. I particularly enjoyed Sherlock, then there's Luther, Marchlands and Downton Abbey, and, of course, the fabulous Doctor Who. I'm currently researching a future novel by watching all the old ITC shows from the 1960s and 70s … The Persuaders, The Protectors, The Avengers, The Champions, The Prisoner, The Saint, Danger Man, Thunderbirds, Departments … I adore that stuff! Tightly scripted pulp fun with lots of British eccentricity!

SS: Holy shit, Black Swan. I once killed a man for dissing Natalie Portman.

MDL: I have two very young kids so I have very little chance to go to the movies. The last thing I saw was the Swedish original of Let Me In - Let The Right One In. It was extremely good, one or two episodes of unintentional comedy aside. Beautifully shot, as they say. Actually, I saw Inception too. Very good but I remember next to none of its details.

Thanks for another interesting round table.

ReplyDeleteI'm addicted to Burton & Swinburne and therefore I have been keen to read Mark Hodder's answers. I highly appreciate his research which find expression in the Burton & Swinburne novels. This is a fundamental part of the charm of the books.

Viva la steam and the punk!

I'm hoping that Burton & Swinburne addiction is highly contagious! Researching the background to the novels is a very enjoyably process, and I hope it results in convincing worldbuilding. I think this is necessary when absurdities like rotorchairs are added ... if the world feels like it could exist, then ridiculous things tend to be rather more acceptable, whereas, with a weakly built environment, the crazy stuff might cause the reader to throw the book across the room (not so bad with a paper edition but potentially costly with an e-reader)!

ReplyDelete